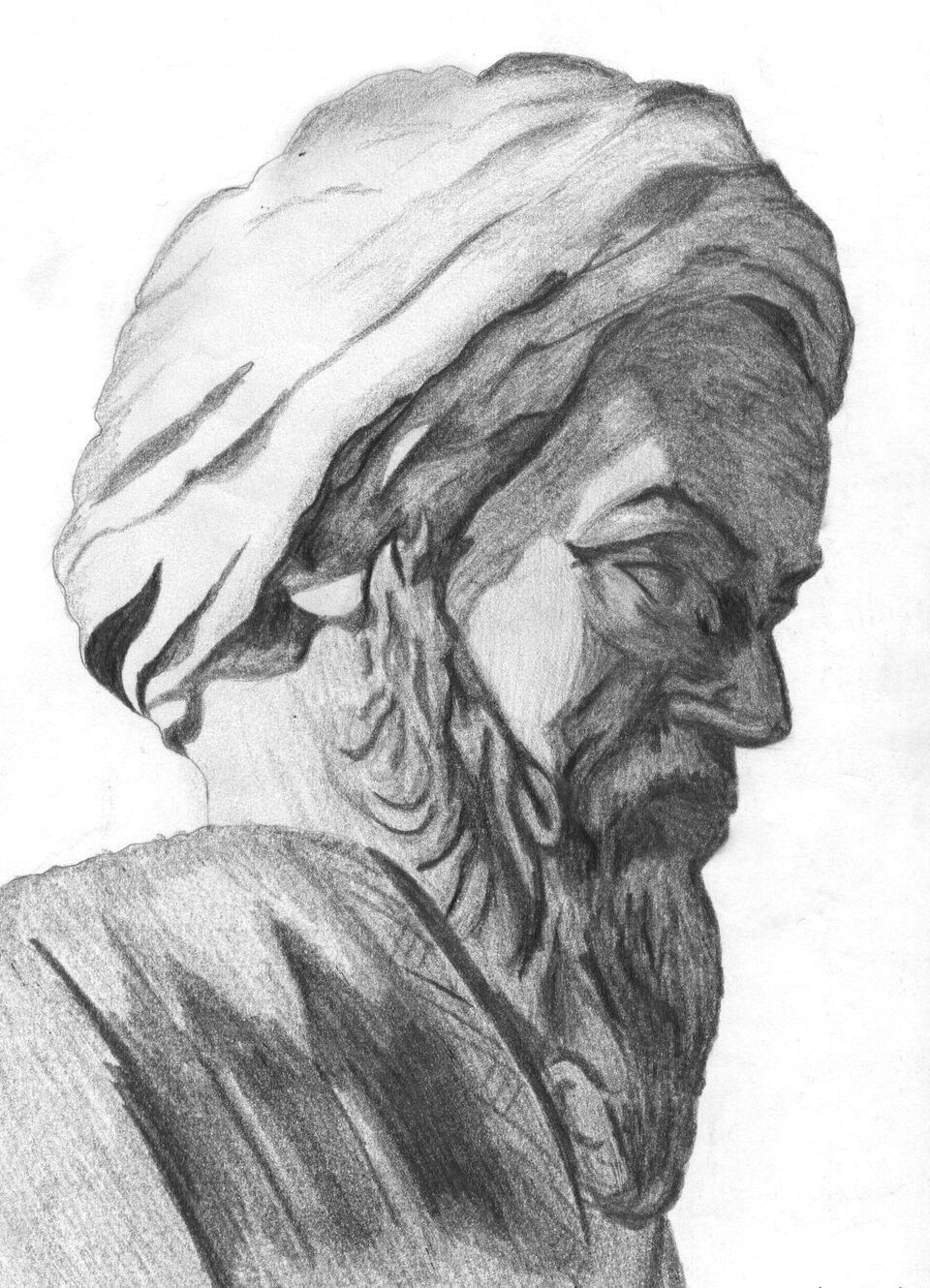

Abu Bakr al-Razi

Category : monumentDocs , philosophyDocs , SpiritualDocs , TranslatorDocs

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī, also known as Rhazes[a] (full name: أبو بکر محمد بن زکریاء الرازي, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī),[b] c. 864 or 865–925 or 935 CE,[c] was a Persian physician, philosopher and alchemist who lived during the Islamic Golden Age. He is widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of medicine,[1] and also wrote on logic, astronomy and grammar.[2] He is also known for his criticism of religion, especially with regard to the concepts of prophethood and revelation. However, the religio-philosophical aspects of his thought, which also included a belief in five “eternal principles”, are fragmentary and only reported by authors who were often hostile to him.[3]

A comprehensive thinker, al-Razi made fundamental and enduring contributions to various fields, which he recorded in over 200 manuscripts, and is particularly remembered for numerous advances in medicine through his observations and discoveries.[4] An early proponent of experimental medicine, he became a successful doctor, and served as chief physician of Baghdad and Ray hospitals.[5][6] As a teacher of medicine, he attracted students of all backgrounds and interests and was said to be compassionate and devoted to the service of his patients, whether rich or poor.[7] Along with Thabit ibn Qurra (836–901), he was one of the first to clinically distinguish between smallpox and measles.[8]

Through translation, his medical works and ideas became known among medieval European practitioners and profoundly influenced medical education in the Latin West.[5] Some volumes of his work Al-Mansuri, namely “On Surgery” and “A General Book on Therapy”, became part of the medical curriculum in Western universities.[5] Edward Granville Browne considers him as “probably the greatest and most original of all the Muslim physicians, and one of the most prolific as an author”.[9] Additionally, he has been described as the father of pediatrics,[10][11] and a pioneer of obstetrics and ophthalmology.[12]

Al-Razi was born in the city of Ray (modern Rey, also the origin of his name “al-Razi”),[13] into a family of Persian stock and was a native speaker of Persian language.[14] Ray was situated on the Great Silk Road that for centuries facilitated trade and cultural exchanges between East and West. It is located on the southern slopes of the Alborz mountain range situated near Tehran, Iran.

In his youth, al-Razi moved to Baghdad where he studied and practiced at the local bimaristan (hospital). Later, he was invited back to Rey by Mansur ibn Ishaq, then the governor of Ray, and became a bimaristan’s head.[5] He dedicated two books on medicine to Mansur ibn Ishaq, The Spiritual Physic and Al-Mansūrī on Medicine.[5][15][16][17] Because of his newly acquired popularity as physician, al-Razi was invited to Baghdad where he assumed the responsibilities of a director in a new hospital named after its founder al-Muʿtaḍid (d. 902 CE).[5] Under the reign of Al-Mutadid’s son, Al-Muktafi (r. 902–908) al-Razi was commissioned to build a new hospital, which should be the largest of the Abbasid Caliphate. To pick the future hospital’s location, al-Razi adopted what is nowadays known as an evidence-based approach suggesting having fresh meat hung in various places throughout the city and to build the hospital where meat took longest to rot.[18]

He spent the last years of his life in his native Rey suffering from glaucoma. His eye affliction started with cataracts and ended in total blindness.[19] The cause of his blindness is uncertain. One account mentioned by Ibn Juljul attributed the cause to a blow to his head by his patron, Mansur ibn Ishaq, for failing to provide proof for his alchemy theories;[20] while Abulfaraj and Casiri claimed that the cause was a diet of beans only.[21][22] Allegedly, he was approached by a physician offering an ointment to cure his blindness. Al-Razi then asked him how many layers does the eye contain and when he was unable to receive an answer, he declined the treatment stating “my eyes will not be treated by one who does not know the basics of its anatomy”.[23]

The lectures of al-Razi attracted many students. As Ibn al-Nadim relates in Fihrist, al-Razi was considered a shaikh, an honorary title given to one entitled to teach and surrounded by several circles of students. When someone raised a question, it was passed on to students of the ‘first circle’; if they did not know the answer, it was passed on to those of the ‘second circle’, and so on. When all students would fail to answer, al-Razi himself would consider the query. Al-Razi was a generous person by nature, with a considerate attitude towards his patients. He was charitable to the poor, treated them without payment in any form, and wrote for them a treatise Man La Yaḥḍuruhu al-Ṭabīb, or Who Has No Physician to Attend Him, with medical advice.[24] One former pupil from Tabaristan came to look after him, but as al-Biruni wrote, al-Razi rewarded him for his intentions and sent him back home, proclaiming that his final days were approaching.[25] According to Biruni, al-Razi died in Rey in 925 sixty years of age.[26] Biruni, who considered al-Razi his mentor, among the first penned a short biography of al-Razi including a bibliography of his numerous works.[26]

Ibn al-Nadim recorded an account by al-Razi of a Chinese student who copied down all of Galen‘s works in Chinese as al-Razi read them to him out loud after the student learned fluent Arabic in 5 months and attended al-Razi’s lectures.[27][28][29][30]

After his death, his fame spread beyond the Middle East to Medieval Europe, and lived on. In an undated catalog of the library at Peterborough Abbey, most likely from the 14th century, al-Razi is listed as a part author of ten books on medicine

Although al-Razi wrote extensively on philosophy, most of his works on this subject are now lost.[47] Most of his religio-philosophical ideas, including his belief in five “eternal principles”, are only known from fragments and testimonies found in other authors, who were often strongly opposed to his thought.

Al-Razi’s metaphysical doctrine derives from the theory of the “five eternals”, according to which the world is produced out of an interaction between God and four other eternal principles (soul, matter, time, and place).[49] He accepted a pre-socratic type of atomism of the bodies, and for that he differed from both the falasifa and the mutakallimun.[49] While he was influenced by Plato and the medical writers, mainly Galen, he rejected taqlid and thus expressed criticism about some of their views. This is evident from the title of one of his works, Doubts About Galen.

The modern-day Razi Institute in Karaj and Razi University in Kermanshah were named after him. A “Razi Day” (“Pharmacy Day”) is commemorated in Iran every 27 August.[72]

In June 2009, Iran donated a “Scholars Pavilion” or Chartagi to the United Nations Office in Vienna, now placed in the central Memorial Plaza of the Vienna International Center.[73] The pavilion features the statues of al-Razi, Avicenna, Abu Rayhan Biruni, and Omar Khayyam.